by Judy George, Senior Staff Writer, MedPage Today September 23, 2020

"Smart pills" and other dietary supplements marketed to boost brain function contained potentially dangerous combinations and doses of drugs not approved by the FDA, researchers found. 5'-Deoxy-5-Fluoro-N-[(Pentyloxy)Carbonyl]Cytidine

Five of these drugs were found in 10 so-called "nootropic" or "cognitive enhancer" supplements tested, reported Pieter Cohen, MD, of Cambridge Health Alliance in Massachusetts, and colleagues in Neurology: Clinical Practice.

All 10 supplements contained omberacetam (Noopept), a piracetam analog used in Russia to treat traumatic brain injury, mood disorders, cerebral vascular disease, and other indications, but not approved in the U.S.

A typical pharmacologic dose of omberacetam is 10 mg; doses in a recommended supplement serving size were as high as 40.6 mg.

"Americans spend more than $600 million on over-the-counter smart pills every year, but we know very little about what is actually in these products," Cohen said.

In previous work, Cohen and colleagues detected individual drugs not approved in the U.S. in supplements, "but in our new study, we found complex combinations of foreign drugs, up to four different drugs in a single product," he pointed out.

"Finding new combinations of drugs that have never been tested in humans in over-the-counter brain boosting supplements is alarming," Cohen told MedPage Today. "We should counsel our patients to avoid over-the-counter smart pills until we can be assured as to the safety and efficacy of these products."

In the U.S., the FDA does not approve dietary supplements for safety or effectiveness before they are sold, but can take action after the products reach the market if they're mislabeled or contain adulterated products.

That may not be enough, noted Joshua Sharfstein, MD, of Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health in Baltimore and a former FDA deputy commissioner, who wasn't involved with the study.

"The laws on dietary supplements should be strengthened to require listing of products before marketing, with the ability for FDA to keep obviously illegal products from being sold," Sharfstein told MedPage Today.

Last year, Cohen and colleagues showed that piracetam, a drug approved in Europe to treat cognitive impairment but rejected by the FDA, was readily available in the U.S. as part of the rising tide of nootropic or cognition-enhancing drugs.

This time, they searched the NIH Dietary Supplement Label Database and the Natural Medicines Database for products labeled as containing piracetam analogs -- omberacetam, aniracetam, phenylpiracetam, or oxiracetam. They found 10 products in the databases: eight were marketed explicitly to enhance mental function, one to "outlast, endure, and overcome" and one as "workout explosives."

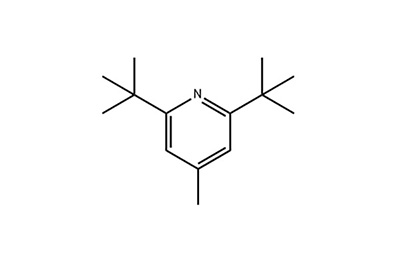

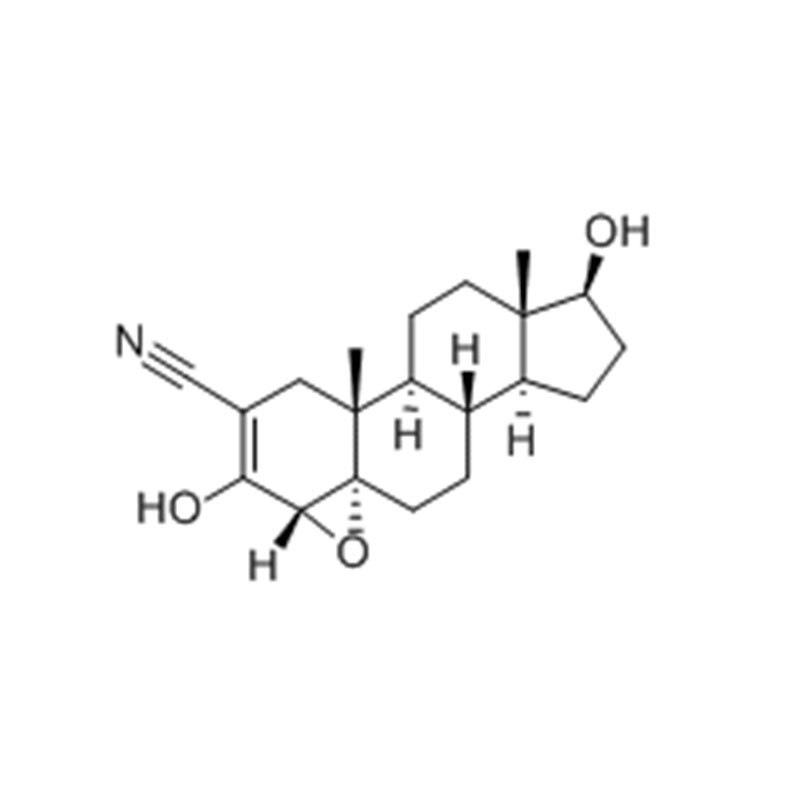

They purchased supplements online in September 2019 and analyzed them using non-targeted liquid chromatography-quadrupole time-of-flight mass spectrometry methods. In the 10 products tested, omberacetam and aniracetam were detected along with three additional unapproved drugs: phenibut, picamilon, and vinpocetine.

Phenibut is a prescription drug available in Russia to treat anxiety, insomnia, alcohol withdrawal, and other indications. Picamilon is a gamma-aminobutyric acid agonist used in Russia to treat cerebrovascular ischemia, mood disorders, and alcohol withdrawal. Vinpocetine is used in Germany, Russia, and China for stroke and cognitive impairment. In June 2019, the FDA warned that women of childbearing age should not use vinpocetine.

Besides high levels of omberacetam, researchers found as much 502 mg of aniracetam (typical pharmacologic dose 200-750 mg), 15.4 mg of phenibut (typical pharmacologic dose 250-500 mg), 4.3 mg of vinpocetine (typical pharmacologic dose 5-40 mg), and 90.1 mg of picamilon (typical pharmacologic dose 50-200 mg) in supplement serving sizes.

Some supplements contained more than one unapproved drug; one product combined four unapproved drugs. Of the supplements that listed drug quantities on their labels, 75% (nine of 12) of declared quantities were inaccurate.

The risks of using specific products are not known although the drugs found in this study have been linked to adverse effects including increased and decreased blood pressure, insomnia, agitation, dependence, sedation, hospitalization, and intubation, the researchers said.

The supplements appeal to people of all ages, Cohen noted. "Young people -- sometimes those working in tech who are interested in 'brain hacking,' but also gamers and many others" -- use these types of pills to increase productivity, he said. "We are very worried about the many seniors who try memory-enhancing products as they might start to struggle with early cognitive decline or normal changes of aging."

The study has several limitations: products were tested at only one point in time, and results are not generalizable to all supplements labeled as containing a piracetam analog.

"It's important to note how we selected our supplements for this study," Cohen said.

"We did not search Google for smart pills. We found these products on the NIH's own website and another high-quality supplement database. The NIH openly listing supplements with foreign drugs is likely contributing to confusion among consumers and clinicians who would have no way to know that these products are not legally sold in the U.S."

Judy George covers neurology and neuroscience news for MedPage Today, writing about brain aging, Alzheimer’s, dementia, MS, rare diseases, epilepsy, autism, headache, stroke, Parkinson’s, ALS, concussion, CTE, sleep, pain, and more. Follow

Researchers disclosed relevant relationships with NSF International, UptoDate, Consumers Union, PEW Charitable Trusts, the FDA, the NIH, the Department of Agriculture, and the International Conference on the Science of Botanicals.

Source Reference: Cohen PA "Five unapproved drugs found in cognitive enhancement supplements" Neurology: Clinical Practice 2020; DOI:10.1212/CPJ.0000000000000960.

Glacial Acetic Acid The material on this site is for informational purposes only, and is not a substitute for medical advice, diagnosis or treatment provided by a qualified health care provider. © 2005–2023 MedPage Today, LLC, a Ziff Davis company. All rights reserved. Medpage Today is among the federally registered trademarks of MedPage Today, LLC and may not be used by third parties without explicit permission.